Top 9 Free Asset Management Software Tools for 2026

Asset management is one of the most common, mission-critical ITSM workflows. Efficiently handling requests for devices helps us to minimize internal admin costs. This ensures that our IT resources are deployed as effectively as possible.

At the same time, we can improve experiences for service users with a centralized, accessible tool to submit and manage requests.

Today, we’re checking out a range of open-source and free asset management software. We’ll be picking out tools from different corners of the market, from COTS applications, to highly customizable solutions.

By the end, you’ll be able to make a fully informed decision about which option is right for you.

But first, let’s start with the basics.

What is asset management?

Asset management comprises all workflows involved in deploying devices to end users. This includes maintenance, monitoring, and lifecycle management.

This can take a few different forms. For example, buying, preparing, and deploying assets as a part of an onboarding process.

However, the core of this is around handling requests for device rentals. That is, helping IT teams to respond to asset requests based on internal business rules and device availability.

On top of this, asset management also requires us to handle device lifecycles. This includes tasks such as scheduling maintenance, patch management, or calculating annual depreciation.

We may even predict usage trends in order to inform procurement decisions down the line

Check out our resource on ITIL asset management.

What do asset management tools do?

So, that’s what asset management means in theory. The next question is, what does asset management software do?

The most basic functionality is providing an asset inventory. This tracks the assets we have, usage data, deployment information, related business rules, and more.

Asset management tools then allow us to build out workflows leveraging this inventory data with a combination of end-user interfaces and automation rules.

So, for example, we can provide forms to service users to to request a device rental. We could then automate approvals based on stored rules and availability or require manual input from our IT team.

IT colleagues and service users must have suitable access to data and actions for their role.

For example, allowing service users to browse available devices and view their own previous requests. But, exposing service-desk colleagues to real-time data relating to all devices and requests.

You might also like our roundup of ServiceNow alternatives.

Why opt for an open-source solution?

There are a few reasons you might prioritize open-source asset management software.

The first is control. Open-source tools offer us flexibility for self-hosting or using existing databases.

We can also expect a higher level of configurability than we would with COTS solutions. So, integrating with other platforms in our ITSM tool stack or enforcing custom business rules.

Security is another key driver for businesses to adopt open-source technologies

A huge part of this is the ability to audit, control, and potentially even internally maintain the source code. Especially for applications that interact with mission-critical data, infrastructure, and processes.

Many businesses opt for open-source asset management tools because of financial reasons. That is, open-source tools can generally be used wholly or in-part for free.

Top 9 open-source and free asset management tools

As we said earlier, we’ve chosen a range of options from across the market for open-source and free asset management tools.

Some offer ready-to-use tools straight out of the box, while others will enable us to build internal tools to match our existing asset information management flows.

Our top picks are

Here’s a summary of what each one offers.

Budibase | Ralph-3 | Snipe-IT | CMDBuild | AssetTiger | OpenMaint | Shelf | AssetFrog | GLPI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Database | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| External Database Connectors | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Public API | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Cloud Platform | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Self-Hosting | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Open-Source | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Free Assets | Unlimited | Unlimited | Unlimited | Unlimited | 250 | Unlimited | Unlimited | 50 | Unlimited |

Let’s check out of our free asset management tools in more detail.

1. Budibase

First up, we have Budibase, the open-source, low-code platform that empowers IT teams to turn data into action.

ITSM teams in all industries rely on Budibase to ship secure, professional workflow apps on any data layer and host them anywhere.

Features

Budibase leads the low-code market for external data support. We offer dedicated connectors for a huge range of relational databases, NoSQL tools, APIs, Google Sheets, and more on top of our built-in database and custom data source plugins. We also offer market-beating functionality, including automation branching, custom AI configs, and powerful database views.

Our visual design tools provide a best-in-class experience for creating end-user interfaces, with autogenerated layouts, custom conditionality rules, optional front-end JavaScript, and a huge library of built-in components and blocks.

Security-focused teams choose Budibase to keep their data secure, with optional self-hosting, free SSO, SCIM support, PWAs, visual role-based access control, air-gapped deployments, and much more.

Use cases

Budibase is the ideal solution for all sorts of ITSM, operations, and other internal tools. Seamlessly connect to your existing asset inventory, no matter where it’s stored, or build a data model from scratch using BudibaseDB.

On top of asset management solutions, our users choose Budibase to build all sorts of forms, admin panels, ticketing tools, workflow apps, approval flows, service catalogs, portals, and much more.

Budibase is fully optimized for busy IT teams that need to output solutions at pace. It’s the perfect solution for systems engineers, solutions architects, data professionals, and other IT colleagues to design and deploy custom tools without overburdening internal development resources.

Pricing

With Budibase, you can build as many tools as you want for free on our open-source plan.

We also offer paid plans with no user limits, starting from $5 per end-user and $50 per creator, complete with synchronous automations, reusable code snippets, custom application branding, and more.

Custom enterprise pricing provides enforceable SSO, air-gapped deployments, environment variables, creator access control, and other key security features.

Check out our pricing page to learn more.

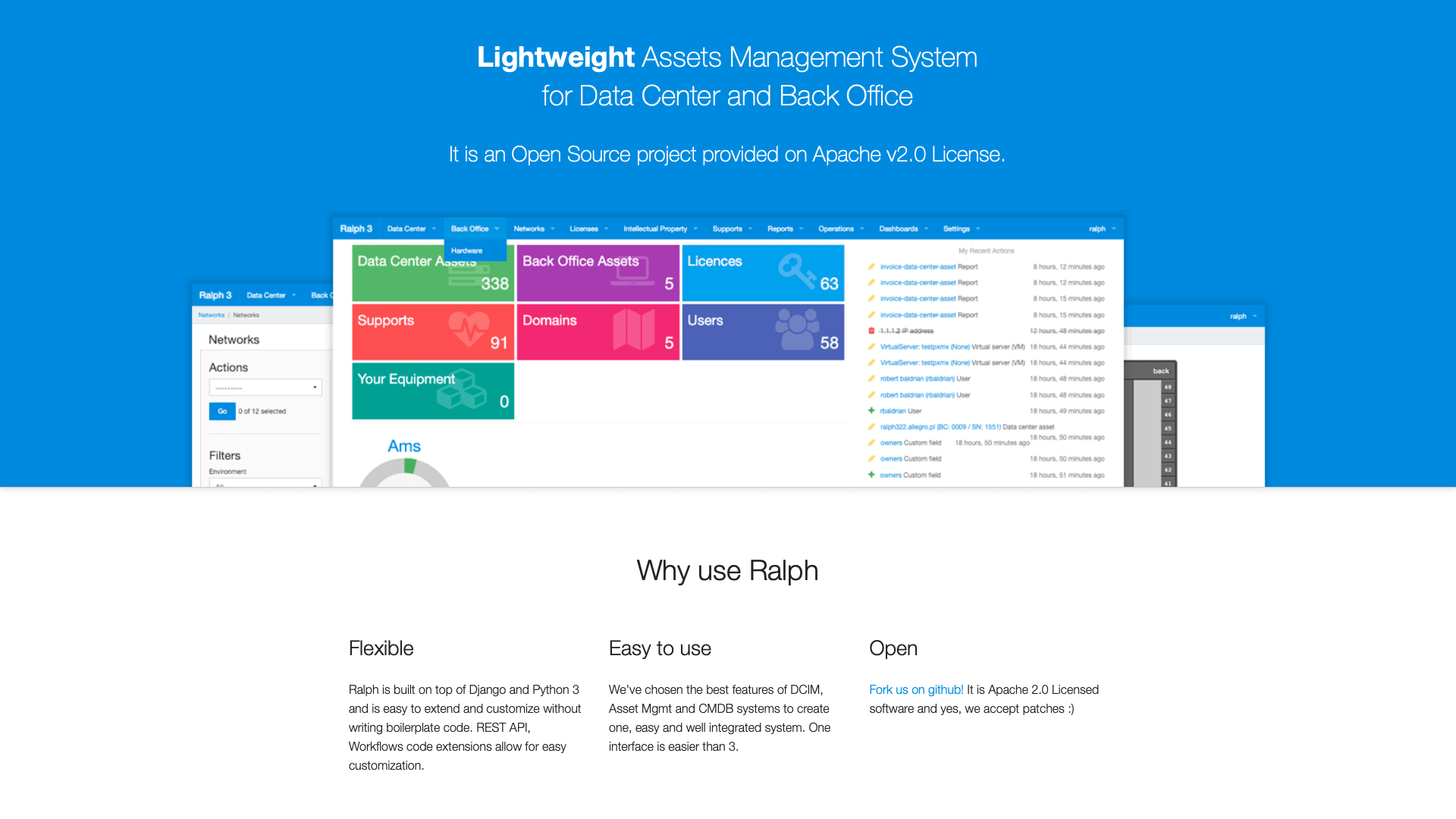

2. Ralph 3

(Ralph 3 Website)

Ralph 3 is a comprehensive open-source asset management tool aimed specifically at data center and back-office use cases.

It provides a high scope for customization, including a powerful API. However, we might need relatively high development skills to get a solution up and running, and its tight focus on managing network hardware might rule it out for other use cases.

Pros

Ralph offers an impressive range of capabilities out of the box, including a dedicated CLI, custom asset fields, built-in domain management, and cloud data syncing.

It’s particularly strong for infrastructure and network hardware asset management, including a range of visualization tools, including network mapping, and up-time monitoring capabilities. We’re really impressed by their tools for visually managing data center hardware.

There are also dedicated tools for managing non-physical assets, including software licenses and vendor support contracts.

Cons

One big downside of Ralph is that we’ll need fairly strong development skills to install and use it compared to some other free asset management solutions. Installation is via Docker, but we’ll also benefit from some familiarity with Python, Django, Ubuntu, and command line tools.

While it’s possible to connect to our own database, this is limited to MySQL support, whereas some of the other platforms in this round-up offer more flexibility here.

It’s also possible to automate certain tasks using the CLI and API connections, but this is a much less mature offering than some other platforms that offer more visual automation and workflow management tools.

Pricing

Ralph 3 is offered as an open-source solution under the Apache 2.0 license. It’s totally free to use, with no paid or premium tiers available. This could make it an attractive option for teams that have the internal resources to configure and manage it in-house.

However, we’ll also need to factor in other costs, including initial configuration, maintenance, and lifecycle management.

Alternatively, we might opt to use an external contractor to handle this, in which case we’ll need to consider the costs related to this.

You might also like our guide to IT asset tracking .

3. Snipe-IT

(Snipe-IT Website)

Snipe-IT is a relatively simple standalone IT asset management tool that’s available as a free self-hosted platform. Or, we can opt to pay for it with managed cloud hosting.

It offers a relatively easy initial set-up, with a fairly easy process for initially configuring the tool to work within common asset management workflows.

Pros

Snipe-IT’s big selling point is that it offers a working solution for basic IT asset management processes pretty much straight out of the box. Most configurations can be carried out using built-in admin settings rather than requiring extensive coding or extensions.

It’s also a strong offering for usage monitoring and reporting. It comes with a range of pre-configured, schedulable reports and dashboards, but we can also write custom visualizations with a built-in query editor.

There are also workable capabilities for related ITSM processes, including incident management, which could make Snipe-IT a good choice for smaller teams whose IT workflows are highly centered on asset management at present.

Cons

One big detractor in Snipe-IT’s offering is its relatively basic, inflexible user interface. This is perfectly functional, but at the same time, it feels a little bit dated compared to some more modern ITSM platforms.

Integration options are also somewhat sparse in Snipe-IT. There’s a platform API, and a couple of first-party integrations for Python tools. Besides this, there’s only a handful of third-party utilities and developer tools, rather than any native integrations for external tools.

Some admin functions in Snipe are also a little bit more complicated than we’d expect. For example, we can create custom permissions and usage policies, but we’ll need to manually edit PHP files to achieve this.

Pricing

Snipe-IT is totally free for self-hosted users. This includes unlimited users and assets, although there are restrictions on API requests and certain features like automatic backups and audit logging.

To overcome these limits, we’ll need to pay for cloud hosting. This is offered on a fixed rate basis, starting from $39.99 per month.

Support plans for self-hosted users are also billed as an optional extra, starting from $499 per year for basic plans up to $4,999 for enterprise customers.

4. CMDBuild

(CMDBuild Website)

CMDBuild is a slightly different prospect. Rather than offering a pre-built solution, it’s an open-source environment for configuring custom asset management solutions.

In other words, it’s a feature-rich configuration management database that includes key asset management functionality including device tracking and monitoring.

Pros

CMDBuild’s core value propostions is the ability to create a centralized, reliable, accessible record of all of our asset data. This can be connected to multiple platforms and tools to create a consistent repository of information.

This offers us extensive flexibility to build advanced solutions for a huge range of use cases, including ITSM, facilities management, fleet management, manufacturing, supply chain, and more.

Additionally, CMDBuild also offers capabilities around creating custom interfaces and workflows for asset management, as well as advanced version control and change management features.

Cons

Desipte being one of the most powerful, flexible platforms we’ve seen today, the big area where CMDbuild falls down is complexity. As such, it may be primarily suited to large enterprises with complex asset data to manage.

It’s also a strong offering in terms of creating a back-end data layer for asset management but may lag behind some other platforms when it comes to creating modern, efficient user experiences.

Some users complain that CMDBuild can be somewhat overwhelming for initial configuration and usage, with the platform’s UIs presenting a relatively steep learning curve.

Pricing

CMDBuild itself is offered for free under the open-source GNU license. As ever, this may be an attractive option, but we’ll also need to factor in the costs of initial configuration, maintenance, and lifecycle management.

Several tiers of SLAs are available, with prices based on usage, support tiers, and specific configurations.

Additional paid services include pay-per-use support packages and training programs.

5. AssetTiger

(Asset Tiger Website)

Next, we have AssetTiger. This is a free, cloud-based asset management platform that we can use off-the-shelf.

It’s a strong offering for teams that need a functional asset management solution with minimal upfront configuration, with the caveat that it may lack much of the flexibility offered by other tools in this space.

Pros

The biggest positive of AssetTiger is that it offers a working cloud-based solution that we can roll out pretty much immediately. This makes it a strong choice for smaller teams with relatively generic ITSM processes that lack the resources for configuring more complex platforms.

It also offers some helpful features for providing sleek experiences to service desk colleagues and end users alike, including asset reservations, communications automations, and native mobile applications.

Compared to some of the other platforms we’ve seen, AssetTiger also offers a modern, attractive interface to interact with asset data and track assets or work orders.

Cons

One key consideration here, however, is that AssetTiger is a closed-source solution, meaning that we can’t easily audit the source code. It’s also only free for up to 250 assets. We’ll explore pricing more in a second.

As a cloud-based solution, AssetTiger can’t be self-hosted, meaning that it will be unviable for security-focused teams where this is a firm requirement.

It also lacks a lot of the flexibility and configurability offered by other platforms, making it comparatively difficult to customize our data model, end-user interfaces, or asset management workflows.

Pricing

AssetTiger is free to manage up to 250 assets. Beyond this, we’ll need to purchase a license, starting from $120 per year for up to 500 assets.

All pricing plans offer unlimited users, meaning that it has the potential to be a very scalable asset tracking software tool.

Importantly, AssetTiger also doesn’t impose feature restrictions across its pricing tiers. As such, it has the potential to be a relatively affordable solution.

6. OpenMaint

(OpenMaint Website)

Powered by CMDBuild, OpenMaint is a free solution for managing facilities, maintenance, and infrastructure. So, it offers great functionality for this niche, but might not be suitable for IT teams.

Pros

Like CMDBuild, OpenMaint offers a highly flexible offering, particularly when it comes to configuring workflows. There’s a visual editor, capable of everything from simple ticket submissions to more complex preventative maintenance workflows, as well as connectors to integrate with external systems,

On top of this, it offers a range of modules aimed at the more granular challenges of managing facilities, buildings, and industrial assets, such as support for geospatial data, energy and environmental analytics, economic management, and more.

As well as a web-based interface, it’s also avaible as an app for mobile and tablet devices, making it a strong offering for teams that need to action asset management tasks in the field.

Cons

Compared to other free asset management tools we’ve seen, the most obvious downside of OpenMaint is that it’s not optimized for traditional IT asset management. This means it’s less likely to be suitable if we’re not dealing with property assets or facilities.

Like CMDBuild, it’s also potentially more optimized for enterprise teams, while smaller organizations might want to look for a more straightforward platform.

Indeed, with a range of modules on offer, some users complain that OpenMaint is overkill for their needs or that it presents a somewhat steep learning curve to get the most out of.

Pricing

OpenMaint is offered under the AGPL license, meaning that we can use, modify, and distribute it for free.

However, we can also pay for professional services and some additional features, including the mobile app, self-service portals, and advanced connector for integrating with external systems.

Quotations are offered on a custom basis, according to our service level needs and the complexity of our instance.

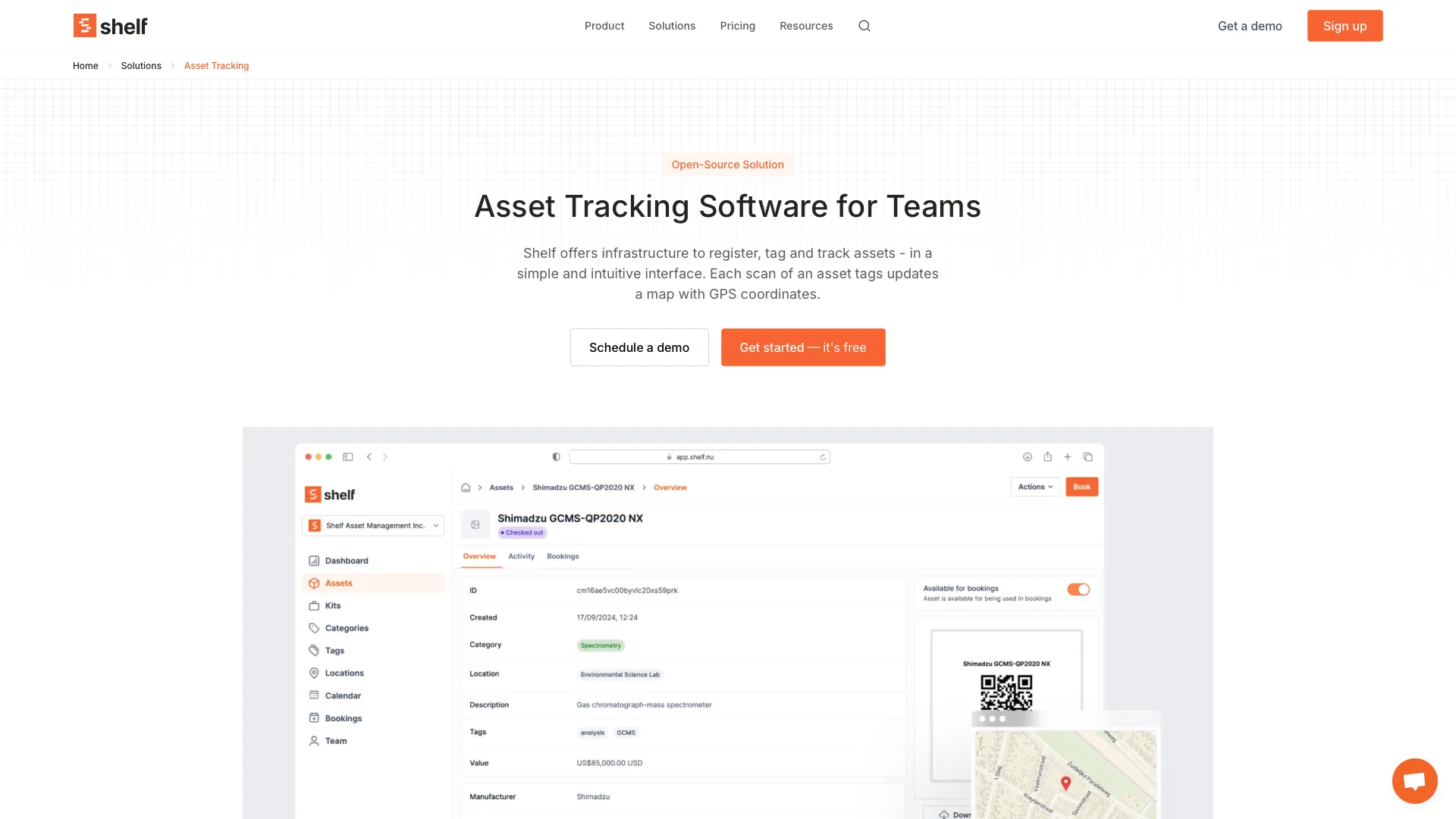

7. Shelf Asset Tracking

(Shelf Website)

Next, we have Shelf Asset Tracking. This is a modern, web-based asset management solution with a usable free tier, making it a strong option for teams of a range of sizes.

Pros

One of Shelf’s clear strengths is its attractive, streamlined UX. It’s based around an intuitive, easy-to-navigate web UI, making it quick and easy to access key actions and insights.

Shelf offers more advanced tagging and tracking than many of the other platforms we’ve seen so far. It offers automatic location tracking for assets when they’re checked in or out via QR code scanning.

It’s also particularly effective when it comes to searching complex asset databases. Shelf offers powerful vector search alongside a huge range of data attributes, making it a powerful solution for keeping on top of large-scale IT estates.

Cons

Despite having a working free tier, one downside of Shelf is that its pricing is somewhat more restrictive than some of the other platforms we’ve seen. For instance, the free version only offers us a single user seat.

As a relatively new platform, we might also find that it lacks certain features. For instance, custom automation capabilities may be less advanced than some of the other platforms we’ve seen.

However, users are quick to note that requested features are often added to the product roadmap, meaning that Shelf has the potential to grow into a highly advanced platform.

Pricing

As noted before, we can use Shelf with a single registered user for free. This gets us unlimited assets. Paid plans start from $190 per year for a single user, with additional capabilities, including working with CSVs.

To overcome user limits, we’ll need a Team license, with unlimited users for $370 per year. We can also add SSO to this plan as an optional extra.

Custom enterprise pricing is available, as well as support-only packages for self-hosted instances.

8. AssetFrog

Next, we have AssetFrog, a feature-rich, freemium SaaS asset management tool.

(Asset Frog Website)

(Asset Frog Website)

Pros

AssetFrog is an attractive option for a wide range of asset management use cases. It offers a clean, modern UI, complete with barcode scanning, document uploads, check-in/outs, customizable dashboards, and asset history logging.

It’s also a particularly strong choice for asset depreciation calculations, with built-in standard accounting methods.

AssetFrog is also a fully cloud-based solution, making it suitable for teams that want to get up and running quickly.

Cons

One downside of AssetFrog is that it’s a fully SaaS-based platform, meaning that we can’t self-host it.

There are also restrictions on the free tier, limiting us to a single user, 50 assets, and three custom fields.

So, you might want to look elsewhere if you need a free asset management software tool for more large-scale usage.

Pricing

Beyond the free tier, paid plans start from $16 AUD per month (around 10 USD) for unlimited users and up to 100 assets.

There are then three pricing tiers above this, with their own respective maximum asset counts.

To track and manage more than 1,000 assets, we’ll need to contact the sales team for a custom quote.

9. GLPI

(GLPI Website)

Lastly, we have GLPI. This is an open-source ticketing and CMDB platform, perfect for a range of asset management tasks.

Pros

GLPI offers a comprehensive CMDB and asset inventory database, providing a centralized experience for managing the full lifecycle of a range of different types of assets, including end user devices, infrastructure, and more.

With GLPI Agent we can automate asset discovery and inventorying, as well as minimizing the manual input that\s required to keep our asset management records up to date.

On top of this, GLPI offers highly effective reporting capabilities, including detailed, customizable reports that give us full visibility into our IT estate.

Cons

Some users report that working with plug-ins can create issues in GLPI, especially relating to versioning and compatability issues.

There are also reports that it can present a steeper learning curve than some other platforms, especially if we opt to self-host.

As GLPI also includes a helpdesk and other related IT tools, some users who want a standalone free asset management tool might find it excessive for their needs.

Pricing

GLPI is free to use under the GNU license.

However, there are also several paid options available. This includes public and private cloud versions of the product, billing at €19 and €21 per agent per month, respectively.

We can also opt for a paid self-hosted license, ranging from €100-1,000 per month, with varying numbers of IT agents and stored assets, as well as a small number of feature restrictions across the tiers.

Turn data into action with Budibase

Budibase is the open-source, low-code platform that empowers IT teams to turn data into action.

With extensive external data support, powerful automations, autogenerated UIs, optional self-hosting, and more, there’s never been a better way to ship professional internal tools at pace.

Non-developers in IT teams rely on our visual development tools to create advanced interfaces in a fraction of the time.

There’s never been a better way to build custom ITSM solutions, including asset management tools, approval apps, forms, portals, ticketing systems, and more.

Check out our features overview to learn more.