Budibase Cloud January 9th Incident

On January 9th, a subset of Budibase Cloud customers were unable to log in. We were able to trace this problem back to data corruption in our production database, and resolved the problem by rolling our database back to a known-good snapshot. The snapshot we rolled back to, at the time we rolled back to it, was 87 minutes old. Any changes made by customers on Budibase Cloud in those 87 minutes were lost.

We regret that we had to do this, and apologise for the inconvenience it has caused. This post is going to discuss in detail how this came to happen, and what we’re doing to prevent it from happening again.

What happened

As part of our ongoing work to make Budibase Cloud a faster and more stable environment, we have been making lots of changes to our technical infrastructure. We’ve added lots of new observability into our platform, we’ve introduced continuous profiling and used this to make a number of performance improvements , and we’ve made changes to our health checks to ensure when tasks become unhealthy, they are replaced.

Another area we’ve been improving is our production database. Budibase Cloud is backed by a database called CouchDB, which we run across 3 servers (or “nodes”). We do this so that if one of these nodes were to go down or have problems, nobody would notice because we still have 2 other nodes available.

We noticed at the start of this year that one of our CouchDB nodes had been configured differently to the other 2. All of the nodes in the cluster should be identical, any divergence in their configuration introduces uncertainty. For example, we found that this outlier node does logging differently to the other two. This makes it trickier to track down problems because now we need to remember that one of our 3 nodes logs somewhere different to the rest of them. What we’d prefer is for them all to work in exactly the same way.

We decided that the easiest way to do this would be to add a new node to the cluster, then turn down the outlier one. We use an “Infrastructure as Code” approach at Budibase, so we have automated processes for adding a new node to our CouchDB cluster.

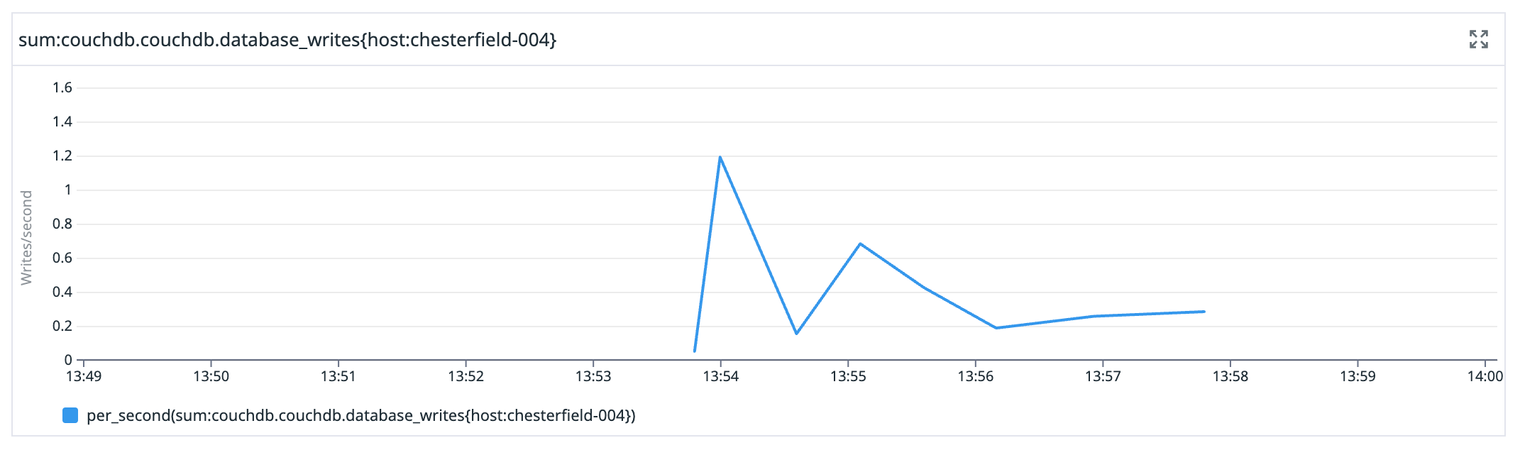

So at 13:52 UTC on January 9th, we add the new node to our CouchDB cluster. Straight away, it begins to synchronise data from the other 3 nodes. This is expected, and can be seen in our monitoring.

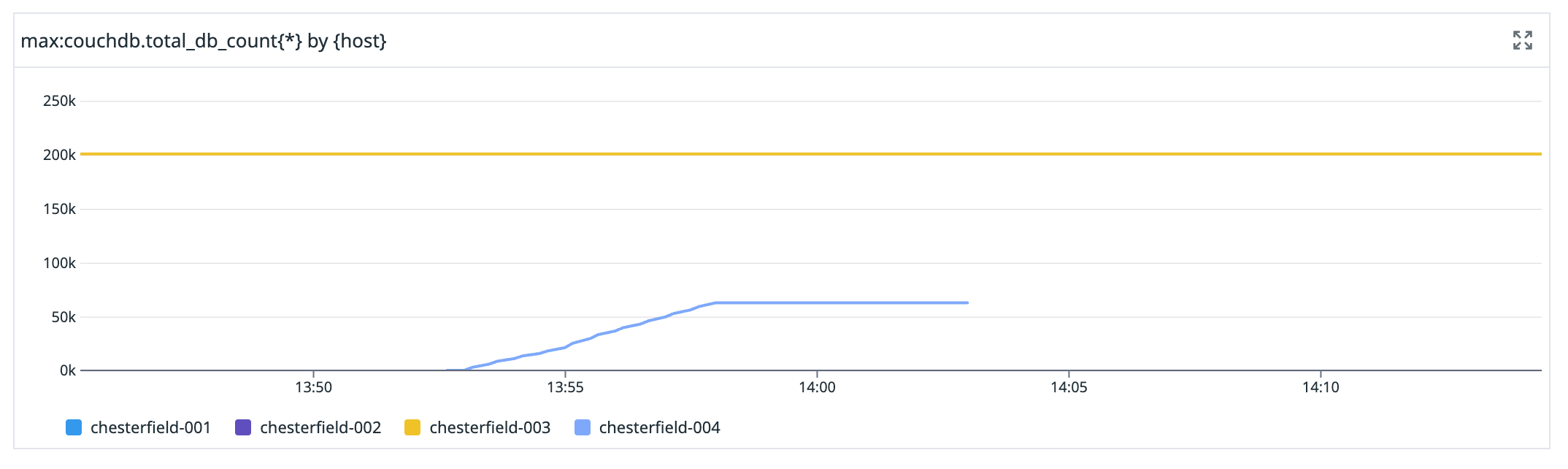

Our production database cluster is called “chesterfield” (after the sofa

), and each of the nodes is numbered sequentially. chesterfield-004 is the new node in this graph. When it first shows up is what it joined the cluster, then we see the number of databases on it slowly increase as it synchronises, then we see the number of databases plateau when we remove it from the cluster, and then the line disappears when the node is turned down.

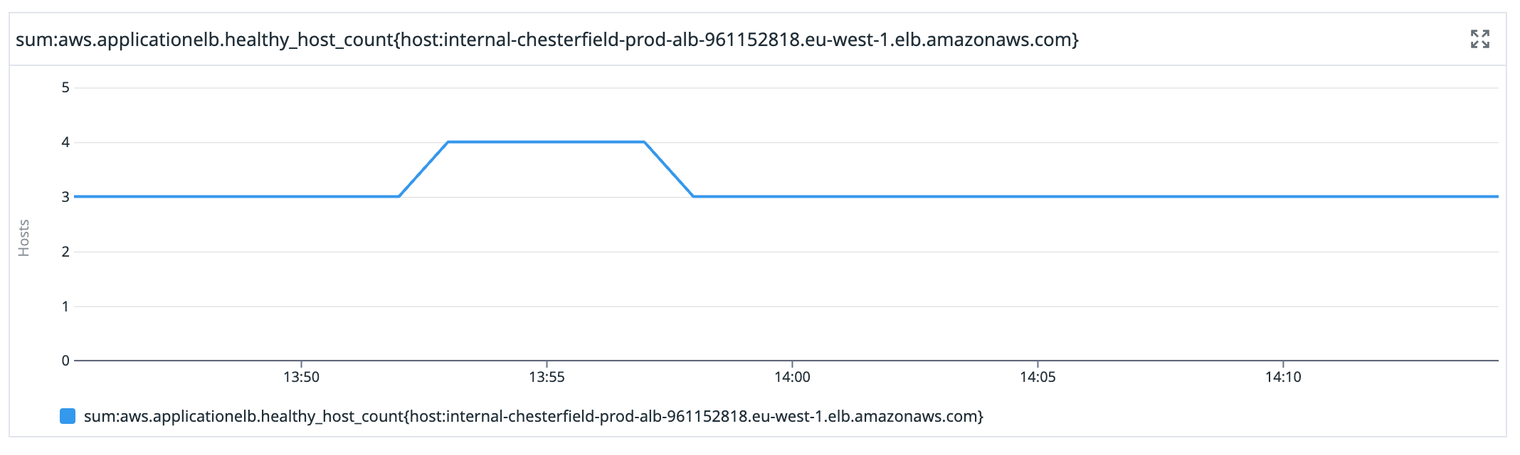

The mistake we made in our automated process for adding nodes was to add the new node to our load balancer before it had fully synchronised. We have a load balancer in front of our CouchDB cluster because any node can service any request, so we round-robin requests between them. You can see that in this graph showing the number of healthy nodes our database load balancer is aware of.

CouchDB is what’s called a “multi-master” database. Many distributed database systems will have one node that’s more important than the others (the “master” node) and this is the node responsible for handling new data, while the other nodes can only handle the fetching of data. This is not the case in CouchDB, all nodes are equal and can handle writes. The way this works under the hood is that conflicting writes, e.g. 2 separate writes to the same data on 2 different nodes, are resolved through a conflict-resolution process.

For historical reasons, most requests that Budibase makes to its internal database first check to make sure that the database they’re writing to exists. If it does not, it gets created. For the 6 minutes that chesterfield-004 was in the load balancer, most requests to check that a database existed would have reported that no, the database does not exist. A new, empty database would be created and the code would continue. This empty database was then replicated to other nodes, effectively deleting all of their contents. We were able to reproduce this behaviour locally, and you can check our methodology here

.

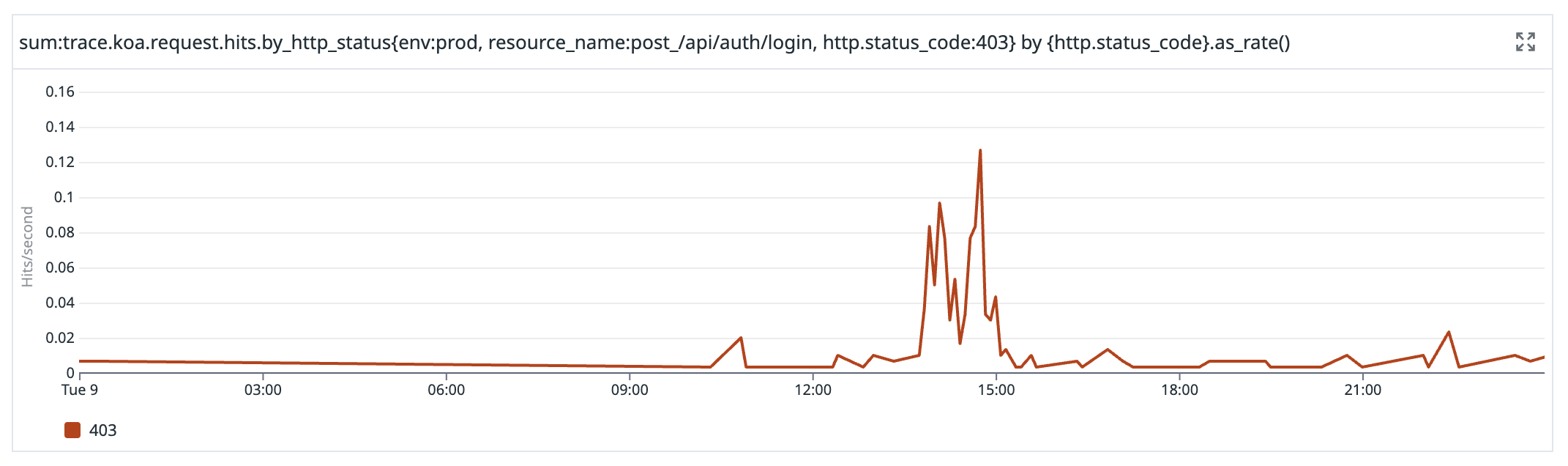

This manifested for most users as the inability to log in, as their user record had been deleted.

Unfortunately we were not aware that there was a problem until 14:13 UTC, when we started receiving reports from customers that they were not able to log in. We do have automated tests of our login process running every few minutes, but they succeeded throughout because the users we use in the tests were not affected.

Why, then, had we removed the node from the cluster and turned it down by 13:58?

When our automation brought up the node, it failed at the point where it was installing CouchDB. We investigated this at the time and found it had used an incorrect CouchDB version string when installing the CouchDB package. We attempted to correct this and re-run the automation, but that didn’t work. This prompted us to bring the node down completely, and start again from the beginning.

This was both lucky and unfortunate. Lucky because we inadvertently fixed what was causing data corruption. The data that had been lost was still gone, but we weren’t losing more data. Unfortunate because when this node went, it took valuable debugging information with it.

How we responded

The first customer reports got to us in the engineering team at 14:13 UTC, and we immediately suspected our work on the database cluster was the cause. The timing lined up perfectly, and it was a substantial change to our infrastructure. By 14:28 UTC we had confirmed data loss in the tenants that had reached out to us and began executing our disaster recovery plan.

We managed to confirm data loss in 11 customers by looking at our records of failed logins, and given that the rate of failed logins was not increasing we believed that without chesterfield-004 in the cluster, the problem was not spreading. However, 11 customers was a lower bound. It was difficult to know what writes had been served by chesterfield-004 prior to it being taken down, and the log files on the machine had not been preserved. Because of this, we decided to play it safe and restore all data to the last known-good backup we had, which was from 13:33 UTC.

We started by taking chesterfield-001 offline and restoring its hard disk to the 13:33 UTC snapshot. When that was done, we re-added it to the cluster and to our dismay it immediately synchronised its state with the other two nodes, re-deleting the data we were trying to restore. Our disaster recovery plan covered partial recovery of data for when we know what we’re restoring, and recovering from a single node failure. There were no steps for rolling the entire cluster back to a known-good state.

At around 15:00 UTC we started to discuss how we could restore the full state of the cluster without incurring downtime. Under time pressure, we weren’t able to find a solution that we were happy with. The best idea we had was to create a completely new cluster, restored from the 13:33 UTC snapshot, and then change our DNS records to point at this new cluster. But that was complex, hadn’t been tested, and would take time.

In the end, we decided we’d have to accept a small period of downtime. The plan was to take chesterfield-001 offline again, restore it to the 13:33 UTC snapshot, but before bringing it back up take chesterfield-002 and chesterfield-003 offline. We would have downtime until chesterfield-001 came back up, but timed well this should only be a minute or two. This way chesterfield-001 would not synchronise to the other two nodes, and we could bring the other two nodes back up shortly after, restored to the 13:33 UTC snapshot.

By 15:39 UTC we were restored, but running on a single CouchDB node. By 15:49 UTC our cluster was fully restored to the 13:33 UTC snapshot and Budibase Cloud was operational again.

We had one problem that persisted after the recovery. Some types of data from our CouchDB cluster get cached in the Budibase app, and during the incident window we had cached some reads from chesterfield-004 that were empty. These cached keys persisted after the cluster had recovered, but we were able to resolve this problem by clearing that part of the cache and allowing it to rebuild from the newly-restored cluster.

What we’re going to do next

This incident has revealed several weaknesses in our processes that need resolving.

- We are going to fix our automation around bringing up new CouchDB nodes and test it thoroughly in a safe, non-production environment. This is an automation we run very infrequently, and in this instance we should have first tested it in a non-production environment instead of trusting that it still worked.

- We are going to write a disaster recovery plan for a full cluster rollback, so that if this happens again in future we will be able to react quicker. Had we had this available to us in this incident, we could have saved approximately 30 minutes in recovery time.

- We were not alerted to this problem automatically, relying instead on the diligence of our customers reaching out to us. It is only through luck that so few customers were affected this time, and we don’t want to rely on luck going forward. We are going figure out a good way to be automatically alerted to data loss situations in future.

- The Budibase code should not be lazily creating databases the way that it does. This is technical debt we have carried with us from the days that Budibase was a desktop app, and it’s time we paid it down. We are going to prioritise work to only create databases when necessary. This change would likely have prevented much of the data loss we saw.

Conclusion

Thank you for reading this incident report. We believe by understanding these incidents in full, coming up with action items that would prevent them in future, and following through on those action items, Budibase will get better every day.